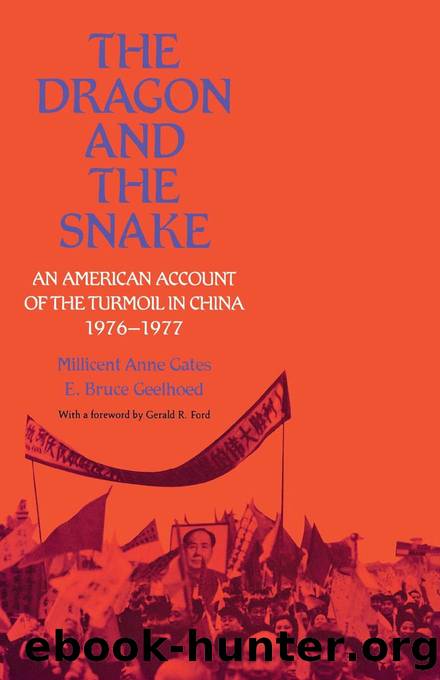

The Dragon and the Snake: An American Account of the Turmoil in China, 1976-1977 by Millicent Anne Gates & E. Bruce Geelhoed

Author:Millicent Anne Gates & E. Bruce Geelhoed [Gates, Millicent Anne & Geelhoed, E. Bruce]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: International Relations, Political Science, Diplomacy

ISBN: 9781512802238

Google: ljuMCgAAQBAJ

Goodreads: 28212471

Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press

Published: 2015-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

VII

In assessing the impact of Maoâs death upon China during the Year of the Dragon, one must note three factors. First, even at the time of his death, Maoâs stature and power in China were so enormous that a power vacuum inevitably developed almost instantly after he died. As Michel Oksenberg and Richard Bush have written,

[Mao] shaped the Chinese communist system so it could be responsive to him. Maoâs power was not totally unconstrained; he had to cajole, threaten, and bargain to attain his ends. Occasionally, he was on the defensive and had to acquiesce to the initiative of others. [But Mao] was the dominant voice; opposition to him carried the risk of political oblivion or worse. . . . To the end of his life, [Mao was] a revolutionary and totalitarian ruler. He believed that the only way to transform China was rapidly, violently, comprehensively; its elites and its institutions would have to be subjected to continual change. . . . In his view, to transform China required vision and extraordinary confidence that a politically motivated Chinese populace, given no respite to cultivate its individual pursuits, could overcome weakness and poverty.41

Second, the point appeared indisputable that Maoâs death created feelings of deep sorrow, as well as deep anxiety, within China. True, his death did not come unexpectedly. True, Mao was a feared and even hated ruler to millions of Chinese who had felt the sting of his wrath during the Cultural Revolution. Even so, his death in September symbolized the latest in a series of national traumas which afflicted the Chinese in 1976. After the earthquake in July, the PRC hierarchy had gone to considerable lengths to staunch the flow of rumors that Maoâs death was imminent. Millions of Chinese, superstitious that an earthquake foretold the end of a regime, were convinced that Mao would soon die. When Mao did die within such a short time of the earthquake, it became more difficult for the Chinese to resist an intense foreboding about their future. As Ross Terrill noted, Maoâs death was a visible demonstration that the dragon had indeed taken China by the throat in 1976.42

Finally, Maoâs death provided the foes of the radicals with the opportunity which they had long awaited. On that point, one must note that the unique nature of that opportunity was not lost on either Deng Xiaoping or his supporters within the senior ranks of the PLA. After being dismissed from his posts in April, Deng apparently found refuge in Guangdong under the protection of General Xu Shiyou, the military commander in the region, and Wei Guoqing, the Partyâs provincial first secretary in Guangdong. Occasionally, Marshal Ye Jianying also visited Guangdong during the summer of 1976 to confer with Deng about plans to prevent a radical takeover of the PRC in the months after Maoâs death.43 Deng and his generation clearly would not surrender to the radicals without contesting them for power, violently if necessary. According to published accounts, Deng and his allies planned

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(35861)

Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair by Susan Sheehan(35550)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32094)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31482)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31436)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(30932)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29445)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18664)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18324)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18269)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14860)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14806)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13828)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13718)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12937)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(12916)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12880)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11970)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11857)